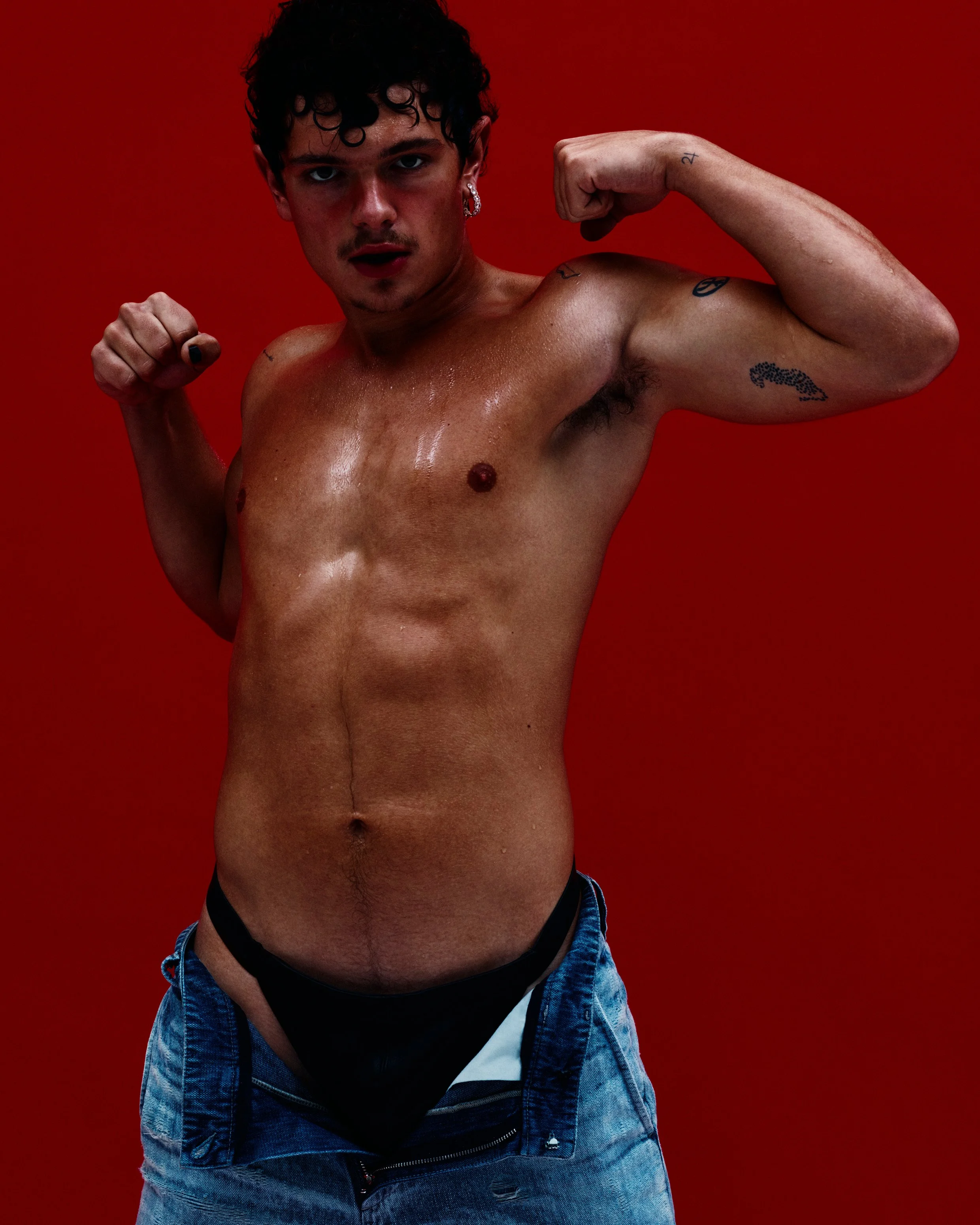

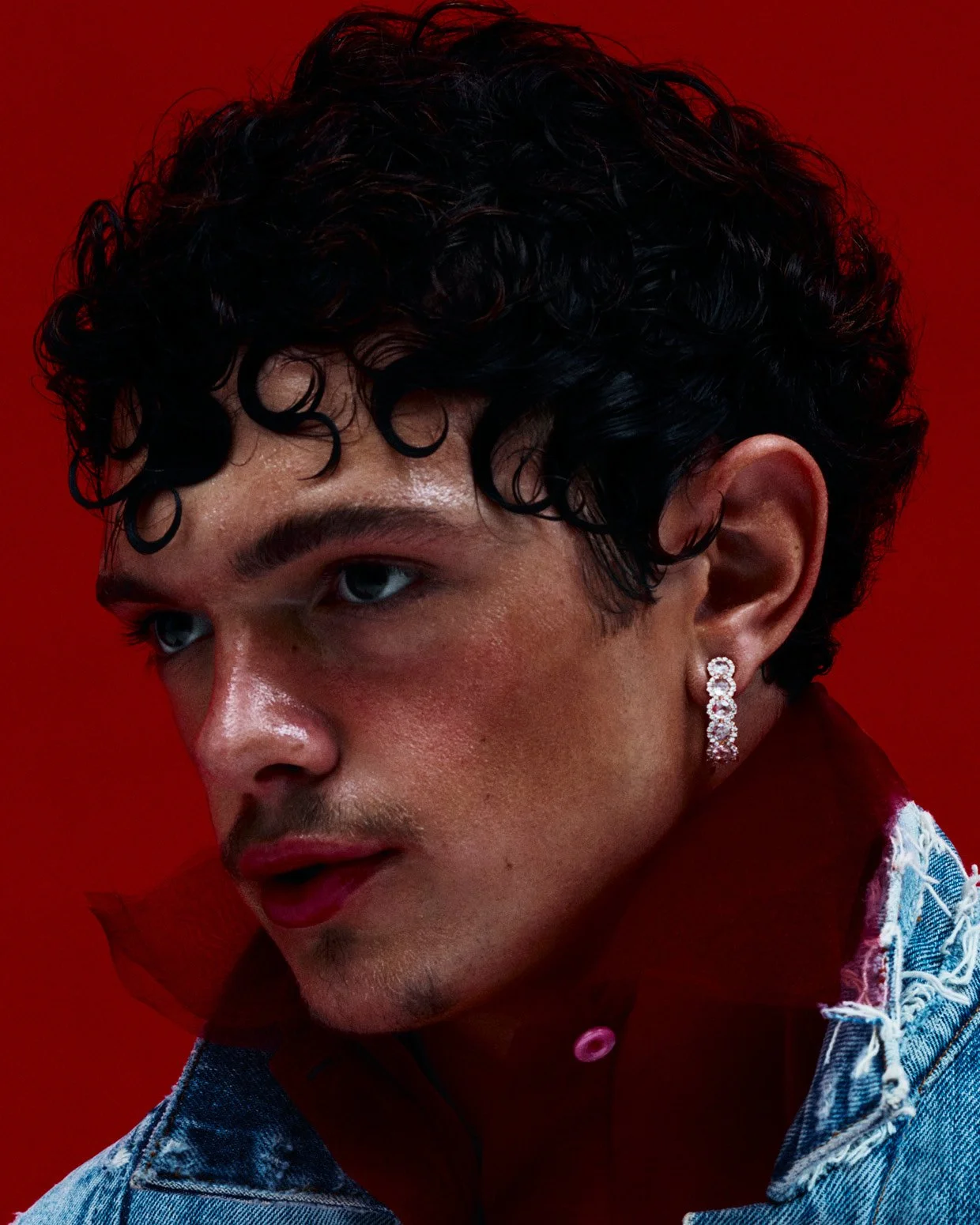

Noah Jupe is in his Shakespeare era for Perfect Issue 10.

Noah Jupe for Perfect Issue 10

Photographer: Rafael Pavarotti

Fashion Editor: Katie Grand

Interview: Paul Flynn

Noah Jupe first saw Hamnet, this year’s serious, muscular awards frontrunner, at the Toronto International Film Festival in September 2025. The film tells the story of how – and why – William Shakespeare wrote Hamlet, in the wake of the death of his young son, Hamnet. A note before the opening scene reminds audiences that ‘Hamnet’ and ‘Hamlet’ were considered the same name in the 16th century. Shakespeare’s artistic crescendo coincides with the period of mourning his deepest life tragedy. How much, if at all, the film seems to ask, do the two intertwine? How big a part can art play in the catharsis we need to survive the most unimaginable heartbreak? Watching the film, I caught myself understanding the raw meaning of ‘to be or not to be’ for the first time. Is it better to live or die through pain? Well?

Noah Jupe, a prodigiously gifted 20-year-old already sporting a well-seasoned CV, plays the actor playing Hamlet during the film’s epiphanic last hour, an evangelical reprisal of the play’s first ever performance. It is not the only strange tangent that the role presented to one of our most exciting young screen talents. ‘Some projects do require more than just you and your imagination,’ he notes, talking on camera from his home in West London. A framed poster for The Deer Hunter sits on the wall just behind him, as if De Niro, rifle in hand, is taking target practise from directly above his right shoulder. Noah is distinguishable mostly by his wide-eyed smile and thick curly hair, painted with a conspicuous, brassy copper dye for the role. His great success in Hamlet, the play within a film, is to attack the role unusually naturalistically. Ironically, given that he is an actor in character for most of his time in it, Noah Jupe is the least actorly component of a very actorly film. It serves the purpose of the picture perfectly.

‘Wow, that’s amazing,’ he says, when I explain that the film was the first time I’d really understood the play. ‘You dive in, but I’d be lying if I said I wasn’t absolutely shitting myself.’ He laughs. Jupe is candid and open. He talks with a scholar’s clarity and a novice’s enthusiasm. He feels like he will make a very comfortable famous person should household recognition eventually bite. ‘I was so nervous. The level of performance here is extremely high.’

Adapted from Maggie O’Farrell’s bestselling novel, Hamnet makes room for career highs for both its leads, Paul Mescal as Shakespeare and Jessie Buckley as Anne Hathaway. This could be the story of any highly strung woman who falls for someone with a propensity towards the spotlight. Hathaway is drawn with a conspicuously witchy, elemental flavour. She is not the model girlfriend. Or if she is, the model is a turbulent conflagration of muse, victim, inspiration, nanny and psychological spirit guide. Her temperament is certainly more Marianne Faithfull to Mick Jagger than Linda to Paul McCartney. Her child’s death is played as a symbolic howl to the moon, of the kind all partners of high-functioning, high-achieving creatives must deliver from time to time. It is a torture told in harrowing physical detail. The camera doesn’t flinch from the ugliness of the plague that kills Hamnet.

If Hamlet is the role actors dream of, silently prepping from the moment they first open its hallowed pages, Noah Jupe was given precisely a week and a half to prep his. He was cast over the phone by director Chloé Zhao while on set filming The Carpenter’s Son, a horror story, on a Greek island opposite Nicolas Cage. ‘I was playing Jesus,’ he notes, as if to solidify the immenseness of the moment. When the call-sheet arrived, he had less than a fortnight to compose himself. Not only had he neither seen nor read Hamlet (‘I read it on the plane home’) – because his life has been on and off film and TV sets since his first casting in A Song for Jenny, a drama about the London 7/7 bombings at the age of 11 – he had never really got to grips with Shakespeare either. ‘You do learn some by osmosis,’ he clarifies, but oh boy, was this his chance to prove something, to himself, to Zhao, to a big, starry cast and to quality audiences.

Noah Jupe was born in London, the eldest of three. The Jupe family moved to just outside Manchester, first Wilmslow, then the Stockport suburb of Davenport, when his mum, Bolton-born actor Katy Cavanagh, was cast in Coronation Street as Julie Carp, a factory owner’s flustered assistant, often in a floral prom dress at Weatherfield’s greasy spoon, Roy’s Rolls. She didn’t encourage any acting dreams in her children. ‘The opposite, in fact,’ says Noah. ‘It’s an industry that is not very forgiving. It can be extremely brutal. If not done in the right way, it can mess people up.’ Nonetheless, young Noah was obsessed by film. ‘I watched a film a day, constantly badgering my mum to let me watch films that I was too young for. She showed me Stand by Me when I was seven. She let me watch Goodfellas when I was a bit older. These films would be the source of my imagination for days after.’

His mum’s agent saw a picture of Noah and passed it on to a casting agent looking for a young actor to fill a role in a Roald Dahl adaptation. ‘I loved Roald Dahl, I loved films and I was having a tough time at school,’ he adds. An audition cycle began. ‘I was like, you know what, if I’m in a film, maybe I’ll be popular. Which, by the way, is not true.’ The minute he was on set, however, he felt something release inside him, the exact inverse of all his pent-up frustrations with school. ‘As soon as I stepped into this other world and saw behind the scenes of basically my biggest passion in life, I was mesmerised. Completely sold. I didn’t even care about any external part of it, I just wanted to be on a set for the rest of my life.’

His dad had to have a word with him in the car home from that first experience of filming. ‘It was a four-hour drive,’ he recalls. ‘He said, “Listen, I can tell how much you’ve loved this. But I have to be pretty brutal right now and say that that might be it, you know? You’ve had an amazing opportunity, remember it for the rest of your life, but you shouldn’t expect there to be more jobs. I don’t want to let you down.” As that dawned on me, I was devastated and cried all the way home.’ The following Monday, the director recommended Noah to a friend, and he booked a short cameo on the macabre Victorian horror chamber piece, Penny Dreadful.

Noah’s first key role was in the John le Carré BBC spy drama The Night Manager. ‘The first day on set I was on a speed boat with Hugh Laurie and Elizabeth Debicki. I was flying around in helicopters. Oh shit, this is serious now.’ Little Noah loved it all. ‘I just had the best fucking time.’ His work was consistent, commercial and good enough to keep him mostly from formal schooling, until a big artistic U-turn arrived in his mid-teens. Shia LaBeouf cast Noah to play the young actor in his fictionalised biopic Honey Boy, an early precursor to the current vogue for stories about how dysfunctional fathers beget dysfunctional sons. ‘It was an incredibly pivotal point. Because it was the first time someone believed in me as an actor, truly.’

With Honey Boy, Noah Jupe became something approaching a star. His fiercely protective parents worried on his behalf about his personal development throughout. ‘It’s funny how movies, some of the most human art that’s ever been created, can be sometimes surrounded by such fake people,’ he says. ‘My experiences making films and TV shows have been incredibly eye-opening. They’ve taught me a lot about what it means to be a human being. I would argue it’s made me a much better person. But there’s also all of these situations that you are thrown in around films which aren’t so lovely and human and… There’s a lot of danger out there. The industry is like a forest. There are some beautiful flowers out there but there’s some wolves too, and you have to navigate through all of it.’

Though emotionally taxing, Hamnet is not a tricky film. It wears its heart unusually clearly on its sleeve, positioning the grieving father, Shakespeare, within a clearly delineated, triangular frame of toxic masculinity. Some of the trickier biographical threads of Shakespeare’s life, including a physically and verbally abusive father who dismisses his creative bent, are woven through the eyes of its effects on the long-suffering wife he more or less abandons in order to follow his artistic heart. Bad grandfather; semi-bad father; what will become of the son? We’ll never know.

‘I think that’s what this film is about,’ Noah says, ‘the cycle of love and grief. What’s really lovely about this film is that you see the character of Shakespeare, who has this awful abusive figure of a man in his life, who is his father, and he is able to break the mould.’ He thinks there is a life lesson contained. ‘That we are able to lean in to all these traumas and turn them into something beautiful.’

Hamnet is a deep read into the cycles of dysfunctional behaviour passed down through XY chromosomes. Old story, current psychological conundrum. Period costume, modern concern. In a year dominated by fresh discourse on the rangy topic of masculinity, in which David Szalay’s masterful Flesh won the Booker Prize, the young teen incel drama Adolescence all the Emmys and Sam Fender’s council estate torpor the Mercury Prize while Oasis established a new super-tier of wealth, status and grandeur for the Northern rock elite, Hamnet feels like Hollywood’s most manful attempt at disentangling the knotty issue of what to do with the testosterone problem, or how to effectively stop treating heterosexual maleness as a crisis.

There are no easy rides here, but that day at the festival in Toronto in September last year must surely have numbered one of the hardest for Hamnet’s generously talented cast. ‘I’m sure there are people who think it’s like trauma porn or something like that,’ notes Noah. ‘But I harshly disagree with that.’ As Zhao understood at that autumnal festival booking, nobody was going to watch Hamnet with the same eyes as Noah Jupe. If she got this reaction right, mass audiences may yet fall into place for a work that feels in the tradition of old, crafted cinema. There is no franchise here. The IP is Maggie O’Farrell and Chloé Zhao’s heads, locked together. ‘One thing I realised while making this film is that love and grief are the same thing,’ he continues. ‘You can’t have one without the other. Eventually something you love, you’re going to stop loving it. Or it’s going to die. If it is true love, then grief will be immense. To learn that, and also to see that through that grief there is a cycle at the end where it is positive again, where you can learn from that grief, where you can almost build more love from that grief? That is the film.’

In the short time Noah prepped and played his first shot at Hamlet, he learned some vital life lessons. ‘In terms of masculinity, in terms of being a 20-year-old man, you know, we really are not thinking about that stuff right now.’ Perhaps we ought to? ‘As a man, you’re not allowed to grieve, really. I live in a family where that’s much more accepted. But I know a lot of people where it isn’t. You’re allowed to cry at a funeral, say, but you’re not allowed to do any weird stuff. Or cry anywhere else. You’re not allowed to get angry. You’re not allowed to express yourself in these moments of grief.’

Like many around him, Noah Jupe worries about the men of his generation. ‘I think I’d start by saying I’m worried about everyone,’ he qualifies. But he’s a young man. He knows the concerns everybody is talking about from the inside. Hamnet floated them all effortlessly to the surface. ‘I think the world is lost and everyone is pretty lost,’ he says. ‘People are trying to hold on to these loose ideas of what they think it means to be a man. But I think that they are two-dimensional ideas. All that social media is creating is figures and gods that we idolise that aren’t real. We’re on this pilgrimage to become these idols that don’t even exist.’

He likes the way some of his peers are articulating fame, undercutting the manner in which social media has distorted achievement into a fuzzy cloud of boastfully energetic, dishonest rhetoric told by a cannon of tribal leaders with nothing but the algorithm on their sides. Was this what they meant by manhood all along?

Inevitably the name of Timothée Chalamet comes up. ‘Chalamet is really interesting,’ he says. ‘I really love that man.’ For symbolic as well as academic reasons. ‘I think that Chalamet is a great hope for the younger generation of actors. He’s someone that represents that movie stars are still possible.’ If movie stardom works, perhaps we understand better the differentiation between truth and fiction. ‘Great work, great choices, I have a lot of respect for him.’ Noah Jupe thinks there is an opening at the moment for a great director to take hold of the great talents of his time, to script and direct a film that nails modern manhood, to establish a new Brat Pack for the roaring Twenties. ‘I think I differ from him, though. To me, I don’t necessarily want to be the best, because I think the best is subjective. I want someone to look at my body of work and think, wow, I can’t believe he played that person and that person. You know? If Timothée Chalamet and Jesse Plemons had a baby, that would be my ideal career.’

The first time we see Noah Jupe on screen in Hamnet, he is delivering the ‘get thee to a nunnery’ speech over and over again, during the first rehearsals for the play’s debut at The Globe. Mescal’s Shakespeare is looking over him, half directing, half scolding him, counting on his every move. The honouring of a life depends on his performance. Many academics have doubted Chloé Zhao’s version of historical events. But whether this is the strict historical truth or not is not the point. Great cinema is about believing in the transformative power of fiction, making the impossible real. She has crafted a story to make hard points about this moment in time, not then. The frustration becomes almost too much too watch.

The casting of Noah Jupe as Hamlet is a highly specific creative blood-letting of life into art by Zhao, placing an unusually sensitive demand on this young actor. Noah’s younger brother, Jacobi Jupe – 14 now, 13 during filming – plays Hamnet in the film, a visual duality connecting the dead boy and his inspiration together. The tromp l’oeil of brother and brother brings a seamless, almost otherworldly energy and intimacy onto the screen, revealing itself only as the credits role and the same surname appears twice. Jupe the elder was very much here for the artistic challenge. One day, Jupe the younger will thank him for it. That role model cycle that exists between men can work in many magical ways.

Effectively, that day in Toronto, Noah Jupe had to watch his little brother die on screen. ‘I had seen little clips of what he had done already from the edit,’ he says. But nothing can prepare you for that experience in a theatre, during the promotional run for a heavyweight drama. ‘Hamnet is the centrepiece of this story. His energy goes throughout this film.’ Noah picked up some cues from Jacobi to play Hamlet, to give the film this essential intertextual twist (Zhao echoes his sentiment by showing a playbill for the first night of Hamlet with the part played by ‘Noah Jupe’, another forgivable historical inaccuracy). ‘I think that’s why it’s so special that I got to do it, because I know my brother so well. When I got to set, I was just like, I want to make sure that that energy is still there and that his spirit is still there through this character, which is the whole message of the story – that through grief can come the most beautiful art and the most beautiful hope.’

In Toronto, watching the edited, soundtracked, completed picture, given his curious, brilliant, bright disposition, his familial connection to the central tragedy of the story and his innate understanding of its wider impact, Noah Jupe steeled himself for the ride. When people talk about the death of cinema, remember these moments. They will matter.

‘I didn’t know quite how special his performance was until I saw it in the cinema for the first time,’ says Noah of his brother. ‘Afterwards, we had to get up and do a Q&A on stage. I knew everyone was coming and they were a bit sad, but they had seen it already. I was absolutely fucking devastated.’ He bumped into Chloé Zhao in the green room. ‘She takes one look at me and she starts laughing and says, “That was the first time you saw the movie, wasn’t it?”’ Her mission was complete. In two members of her cast, she had achieved everything she desired from her audience.

Noah says part of the reason he has allowed himself to think about the surrounding issues of Hamnet, of toxic masculinity and its preponderance to survive – all this material about men in crisis that the film throws elegantly and dramatically at the screen, up there for a contemporary audience – is because he himself is not short of male role models. He has one in particular that he has always looked up to. ‘I definitely do,’ he says conclusively. ‘I’m extremely lucky to have the best role model in the world, which is my father.’

Why?

‘My father is a truly incredible man. As I get older, I start to realise that more, because I start to see him as a friend. When you’re a kid, you obviously look up to your father, you obviously think the world of him. But now I’m older, I have a side to me that looks up to him and idolises him, then there’s also this other side of me that is becoming friends with him, as human beings, totally outside of that. And through that side I’m now seeing, from an external place, how good a man he is, how respectful and kind and generous and loving he is. You don’t really need someone else when you have someone in your life like that. You know?’

That’s beautiful. Would you say that to him?

‘One hundred per cent.’