Melanie Ward: Always Now

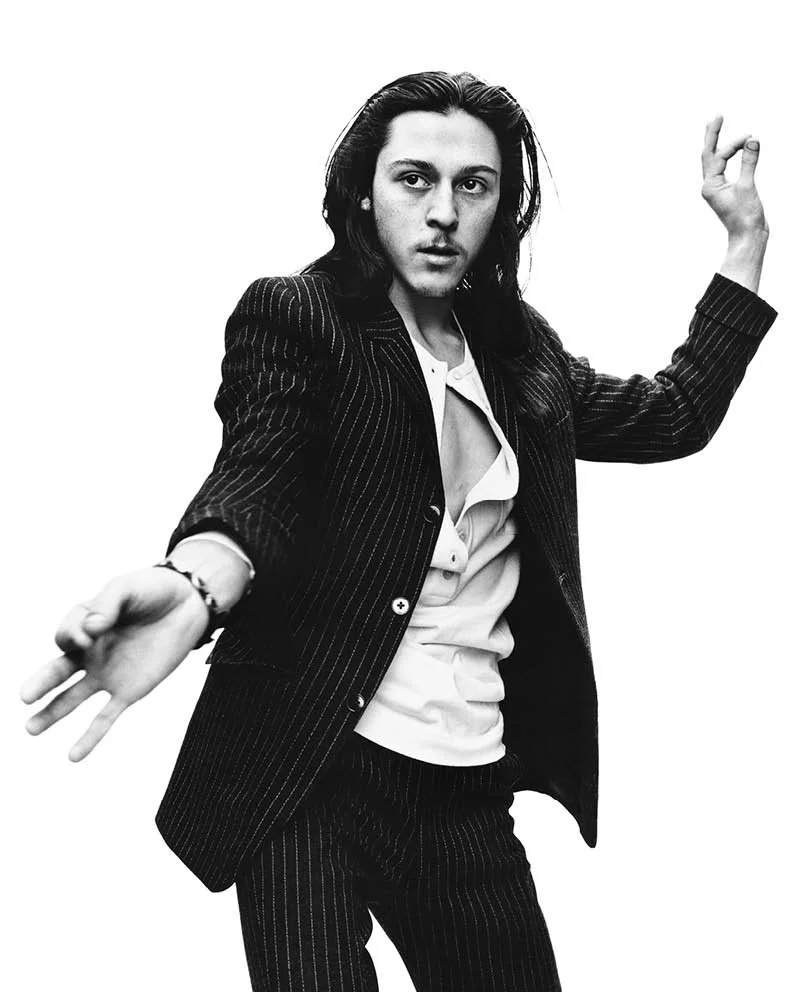

Cover: Photography Inez & Vinoodh, 2003

Writer and Interviewer Jo-Ann Furniss

On 22 October 2025, the stylist Melanie Ward died. Melanie’s loss is immeasurable, both for her friends – many of whom appear in these pages, both in front of and behind the camera, and in this piece – as well as for the fashion industry as a whole. Yet her remarkable visual legacy lives on.

The idea of the ‘fashion moment’ is often mythologised. It is about capturing lightning in a bottle; it is of the time, utterly decisive, saying something about the moment it was created, yet displaying an uncanny, out-of-kilter quality, something always ‘now’. The stylist Melanie Ward was the maker of and contributor to many defining fashion moments – so many in fact that looking back at her images and shows today is both exhilarating and head-spinning. Melanie herself did not like looking back and refused to bow at the altar of nostalgia; she thought of herself as a modernist who always lived and worked in the now. Yet here we are, looking back on her career as a stylist, explaining her impact and trying to communicate how radical yet effortless, spectacular yet hushed, defining yet open-ended what she did is.

There is the famous quote by William Faulkner, ‘The past is never dead. It’s not even past.’ This is what I think of when I look at what Melanie did: the shows, the clothes, but particularly the images she worked upon. They could have been done yesterday, today or tomorrow, and in large part this is because of what Melanie brought to them. More than clothes, she brought a new, radical attitude, stripped back yet full of life, of the moment yet utterly timeless, the ordinary made extraordinary, made fashion. That’s because Melanie was an image-maker; she was a stylist who more than deserves a share of the photographic signature, someone who defined the look of an era and visual culture as much as any photographer, and might well be the reason we even know what a stylist is today. She was the first one labelled a ‘superstar’ as this new role went global.

‘For all of us who have a creative flow, there are moments, objects and people who got our minds clicking in a different way. It has a neurolinguistic reprogramming effect. Melanie’s contribution to culture is in that vein,’ says the curator, writer and photography critic Charlotte Cotton. ‘She created the visuals of our time. She participated in and collaborated with others to make them. These are the seeds for what happens now. This is what real cultural innovators do.’

To credit a stylist with an equal share of the image-making process is not really the done thing in fashion, with its strict hierarchies and codes of creativity. Charlotte Cotton is one of the few curators to do so, particularly in her seminal exhibition Imperfect Beauty, which took place at the V&A in 2000. It is an exhibition that remains radical in its rigorous approach and says more about the present than other relatively recent shows. From being a teenager at the beginning of the 1990s, when I first became aware of Melanie Ward’s work through the pages of magazines like The Face, I can’t help but credit her in this way too. The images she worked on have a magic like nobody else’s; they generated an impression that has never quite left. Her fashion images, still so fresh and alive, have been a constant inspiration for my professional life – even though I am not a stylist. They are one of the benchmarks by which everything else is measured: how to achieve an attitude, a feeling, a resonance and an emotion through fashion, no matter what medium you may work in to convey it. And I am not alone. Seeing these images in style magazines opened up a world of possibilities for many of us.

Melanie Ward had the good fortune / extremely bad fortune to rise to prominence as part of a generation whose work existed almost entirely in print and on the catwalk during its first 10 years. These years were neither extensively digitally documented nor widely accessible online, and this remains the case. It gives the period's work a dream-like quality that persists in the imagination of those who paid attention to magazines at the time. Yet it is a great shame that a younger, digital generation can only experience this work intermittently through books and the occasional scanned vintage magazine. It was an incredibly special moment in fashion, of genuine significance: the rise of Helmut Lang, David Sims, Corinne Day, Kate Moss... All of whom Melanie shared defining professional and personal relationships with and was inextricably linked to their rise in prominence, alongside a whole slew of other designers, photographers and models, all defining something radical, something new.

Yet perhaps the relationship between Melanie Ward, Corinne Day and Kate Moss deserves special mention here. Each member of this startling female triumvirate found her individual place in the image-making process, triumphing and producing some of fashion’s seminal images, both together and apart. Kate Moss first came to real attention as a 16-year-old, modelling alongside photographer Corinne and stylist Melanie in a story that became a Face cover. She will forever look out from that cover, giggling in her famous feather crown, placed on her head by Melanie and monumentalised by Corinne. It was July 1990, and a new, ruling aesthetic had arrived that would change the fashion industry and visual culture as a whole, and teenage Kate would be its queen. She still reigns.

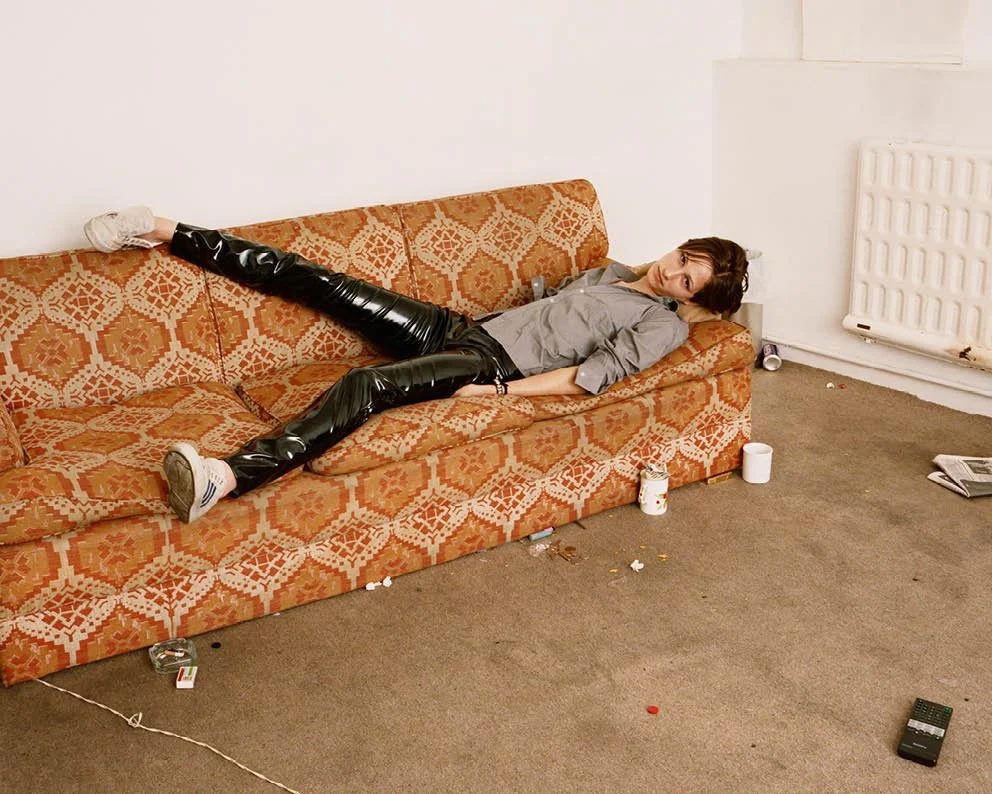

All Photography: Corinne Day

All Styling: Melanie Ward

‘They’d say to me, “Come on you, we’re going to change fashion,”’ says Kate Moss of Melanie and Corinne.

They’d actually say that to you on shoots from the beginning?

‘Yes.’

And you did.

‘Well, they did.’

Really, you all did.

The idea of fashion magazines seemed quite old-fashioned in the Britain of the late Eighties and early Nineties, the place where and when Melanie’s work first emerged. The impression was, they were solely populated by daft, posh girls, with Absolutely Fabulous capturing the vacuously posh editorial meeting in all of its glory. Perhaps the exception was British Elle during that period, where Anna Cockburn materialised, the other great stylist who defined the look of the decade. But it would be British style magazines, predominantly The Face and i-D, that were the real crucibles of this particular revolution. The revolution would then go global, spreading to fashion magazines and reconfiguring the industry in its entirety, approaching ideas of beauty, authenticity and reality anew, something that has never quite left and something many of us felt we could be a part of. At the heart of this was Melanie Ward. It was that Face cover with Kate Moss and Corinne Day which might be seen as this particular aesthetic revolution’s ‘Big Bang’.

Even though it would be later labelled ‘grunge’, it is more accurate to talk about this moment in fashion photography as the equivalent of punk in music, with all the portent and repercussions of that particular movement. There was even a similar dimension of moral panic and outrage. Who were these lower-class upstarts? How dare they be so skinny and snot-nosed! What on Earth were they wearing? Are they all on drugs? It is now quite hard to imagine how some pages featuring non-designer and second-hand clothes in style magazines, with teenage models and photographers and stylists in their early twenties, could have impacted visual culture so radically and in its entirety. So much so that later in the decade, there would be newspaper headlines and TV debates about ‘heroin chic’.

‘I actually had good posture before I met those two’, deadpans Kate Moss of the visual approach and ‘artless’ gestures she was asked to adopt by Corinne Day and Melanie Ward. That radical notion of just being herself, a girl from the London suburbs, ordinary yet extraordinary, in a fashion picture, would change everything. The teenage Kate was meant to be the antidote to the supermodel, yet her impact was so seismic, she would become the most super of them all.

‘They’d say to me, “Come on you, we’re going to change fashion’

-Kate Moss

The subject of the unglamorous suburban sprawl would frequently reappear in what Melanie did in the early days – she too was a working-class girl from the London suburbs. There was something of a poetic and British fuck-you in what this wave of photographers, stylists and models was doing. There was an element of class war in the provocation and elevation of the everyday; here, the things not really allowed in the extravagant realms of traditional fashion now waltzed their way in, just as they did.

The story that is perhaps the full embodiment of this is Nigel Shafran’s defining shoot with Melanie Ward: ‘Teenage Precinct Shoppers’. Appearing in i-D in 1990, the suburban shopping centre shifted into the pages of a style magazine, becoming both subversive and exalted. i-D’s street photography usually featured individuals with a certain extravagant, ‘fashion-forward’ elan, more at home in St Martin’s College than an Ilford shopping mall. Here, positioned as a fashion shoot and completed over weeks rather than days, the participants were not styled by Melanie, only chosen by her and Nigel; the extravagance was in the elevation of their normality and nonchalance.

‘I’d point at someone and Melanie would approach them and explain that we were taking their picture for a magazine,’ explains Nigel Shafran. ‘They were working-class kids we wanted to give visibility to in a magazine; we liked the way they looked, we didn’t change them. I think they look like Roman busts in the pictures; we wanted to elevate them. It was also about consumerism and my thoughts on that; the title is connected to Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles.”

He continues: ‘The shoot wasn’t a commission; we just did it. Melanie and I had a similar sensibility at that time – find something interesting and don’t fuck it up, don’t let your ego get in the way. There was no great thought to it; we just did it. It was innocent and not disrespectful – we both had similar backgrounds, and it was a reaction to what we’d been around in fashion. The work we did together then, in our early to mid-twenties, was our formative years. It was like our first album.’

All Photography: Nigel Shafran

All Styling: Melanie Ward

‘Melanie and I had a similar sensibility at that time – find something interesting and don’t fuck it up, don’t let your ego get in the way. There was no great thought to it; we just did it.’

-Nigel Shafran

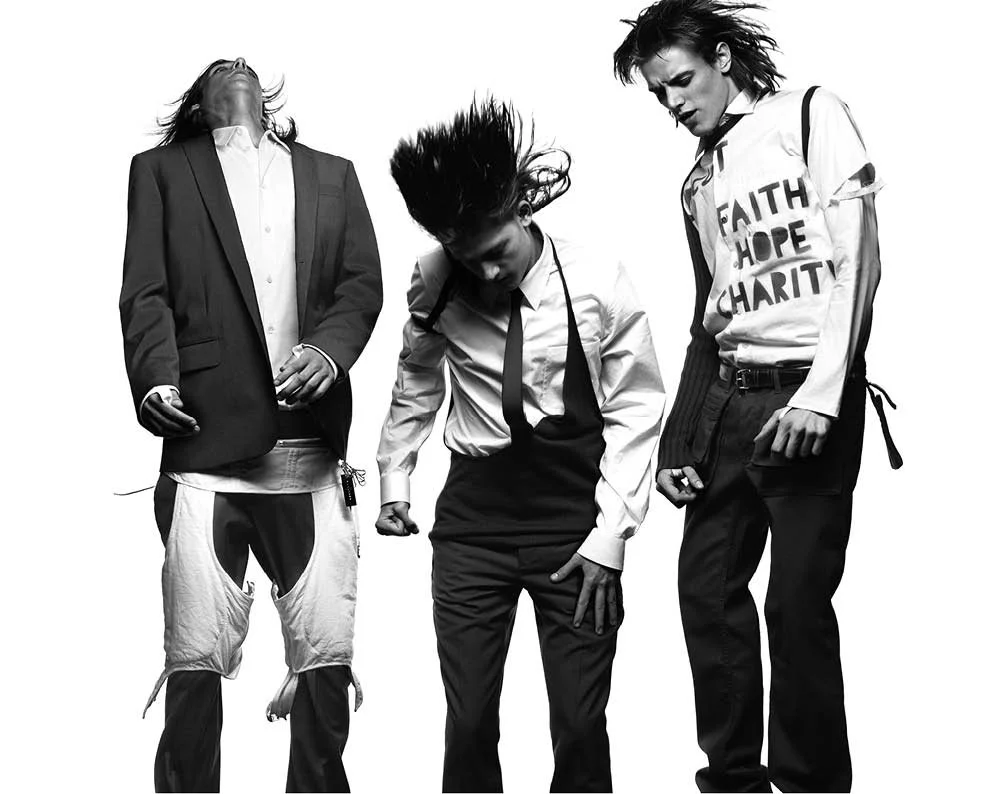

‘A type of revenge!’ declares David Sims of the similar concerns driving his photography and work with Melanie at the time. He is only half joking. It is a preoccupation with levelling a playing field between classes and media, feelings and thought, that has imbued his work throughout his career, and has arguably made him the most influential fashion photographer of his generation. ‘Nothing is made in a vacuum. Our work was in parallel to a shifting club scene and music scene. I actually thought there was such a slow uptake in what we were trying to do.’

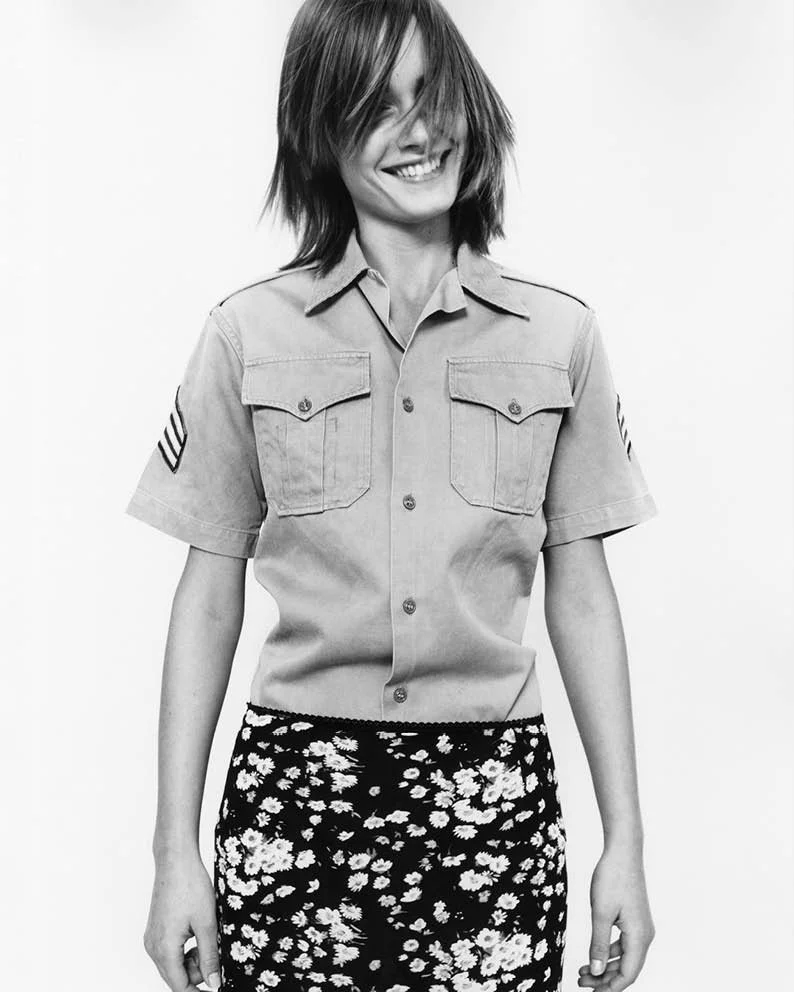

He continues: ‘Energy transmits in good work. We weren’t avoiding risks, we were oblivious to them. Melanie was quite covert; she would fixate on things and had a determined value to what she did. She took delight in being obtuse, oblique and iconoclastic.’ A Ward signature became the delights of clothing to be found in John Lewis’s school department and the sex shops of Pigalle, sometimes paired together, yet never once playing to sexy schoolgirl or boy tropes. Rather, there was always a strange economy and elegance in this very Melanie melange.

‘What she brought most of all was an open heart and a deep pleasure – she was never nervous in being creative. Melanie worked with us all quite differently: whether it was on one of Nigel’s meditations on suburban London or Corinne’s very feminine – but not the hyperfemininity of fashion magazines from that time – almost sapphic worlds. I was always trying to photograph Iggy Pop – really, it all went back to him. Melanie allowed me to live out that fantasy.’

This open-hearted collaboration in the creation of worlds was something Melanie also applied in her work with designers, particularly Helmut Lang. ‘I think she opened a British, working-class reference point for Helmut,’ David explains. ‘We had certain subcultural tropes in what we did. Helmut remade the British Crombie coat and Farah trousers in his own distinct way.’

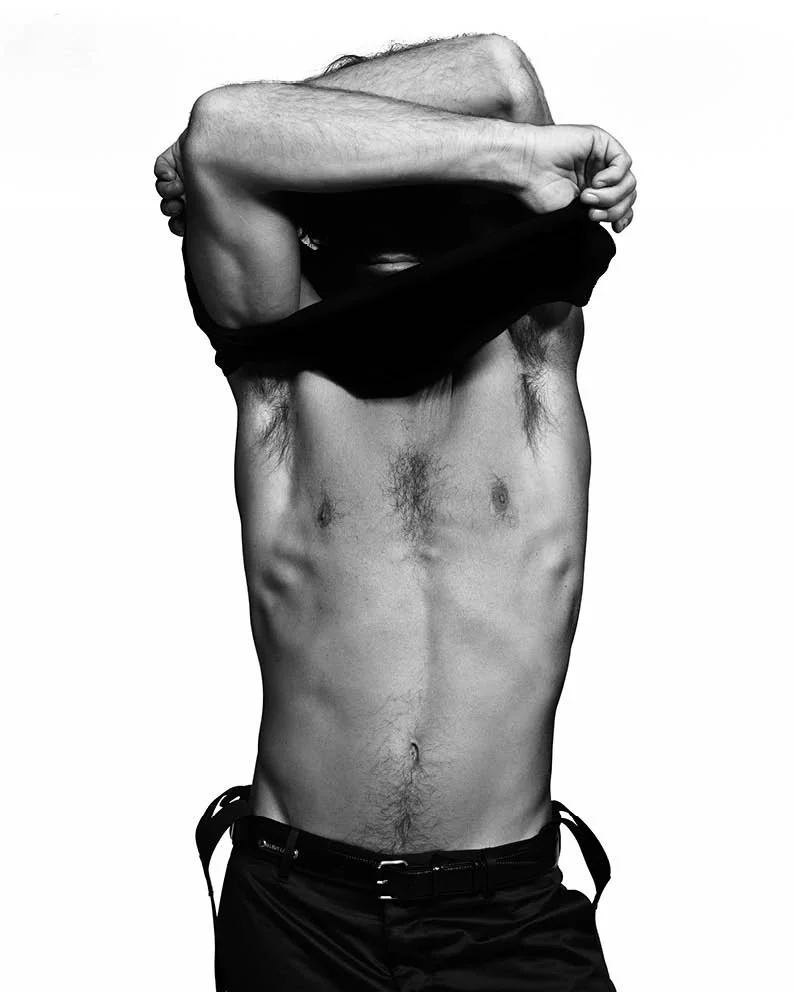

All Photography: David Sims

All Styling: Melanie Ward

‘We weren’t avoiding risks, we were oblivious to them. Melanie was quite covert; she would fixate on things and had a determined value to what she did. She took delight in being obtuse, oblique and iconoclastic.’

- David Sims

‘As a group, we were more focused on the nuances, on the hidden being revealed and celebrated,’ says Guido of these breakthrough years and his own reevaluation and revolution in what a hair stylist could bring to images and shows. ‘It was making the viewer question what fashion was, what beauty was. To question all of it. Melanie spearheaded that.’

He continues: ‘All of us in that group understood the innocence and awkwardness of style, of getting things not quite right. Melanie gave clothes an attitude; she had a knack for trusting normality to make them special. David [Sims] says we were all like a band that worked together. We all added our bit, our instrument to create the music. We were all working to the same rhythm, and David was a great conductor of that band. We didn’t have the pressure of success – we weren’t successful at first! It was Calvin [Klein] who was a big part of the eventual success by picking us up and supporting all of us in America. I suppose that’s when we went off as solo acts.’

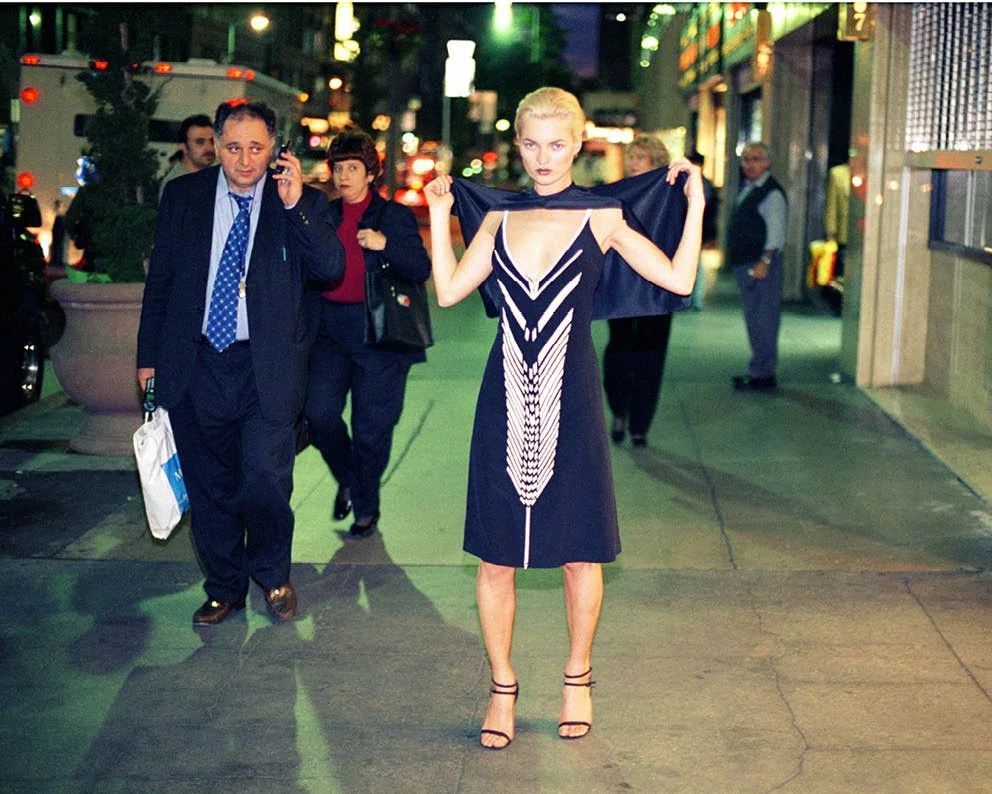

Talking about Melanie and her milieu is like talking about a band that has its indie and alt roots in Britain, but goes global and fills stadiums, particularly in the USA. Melanie herself, as part of this band, was the first fully acknowledged superstar stylist, defining a role for the modern era, encouraging generations to follow her in this newly minted ‘profession’. Of course, America came calling in the form of Calvin Klein and Harper’s Bazaar; she was part of a second golden period for both. Meanwhile, Helmut Lang moved his base of operations from Vienna to New York and their mesmeric working relationship continued and beguiled.

‘I think they were definitely a force for change. But it wasn’t aggressive; they were steadfast in their beliefs and did not waver for a second, not for a second,’ explains Rose Ferguson. ‘I remember being in New York modelling, on a Barneys job with Mel, Corinne and Ronnie Newhouse, and it was hilarious. The pictures were great, but it was so funny just trying to shove a square peg into a round hole. It’s New York, it’s America – things had to be quite “clean”. People were like, “What the fuck’s going on? You’re wearing what? We’re in a studio.” But they never wavered, ever. And Mel never compromised – not in a stubborn, horrible way, but she wouldn’t budge.’

In fact, it would be Melanie and her milieu who would turn America and the rest of the world to their way of thinking. ‘Everyone was an individual, and the look was in combination with the person it was being placed on; it reflected that person. So if you think about the pictures, Kate was very Kate and I was very me. They were photographing the person for fashion, but it wasn’t like photographing fashion for appraisal.’

Rose continues: ‘I remember later, there was a New York Times headline with some of Mel’s pictures saying something like, “Is this a boy or is this a girl? Is she on heroin?” And that ended up under my mum’s eyes. It was all totally unfounded. Later still, I was in a show in New York, and Linda Evangelista was in it too. She said, “Oh, you’re the one.” I look back now, and it feels like there was a collision between traditional glamour and this punk rock fashion, striding through and obliterating everything in its way.’

‘People were like, “What the fuck’s going on? You’re wearing what? We’re in a studio.” But they never wavered, ever. And Mel never compromised – not in a stubborn, horrible way, but she wouldn’t budge.’

- Rose Ferguson

‘I had worked with Melanie when I was creative director at Barneys,’ says Ronnie Cooke Newhouse. ‘I told Gene Pressman [the CEO, who was also hugely involved creatively], “Let me work with Melanie, Corinne and all these new people.” I said, “If you don’t like it and think I’m wrong, then you can fire me.” That’s how I convinced him to do it. He said something like, “If you’re stupid enough to quit your job over it…”’

Ronnie Cooke Newhouse began a long-term working relationship that became a close friendship with Melanie from then on. It would be Ronnie who would introduce Melanie to Calvin Klein, both the man and the brand, when she became creative director there.

‘Calvin took a liking to Melanie. They worked on the main collection together,’ confirms Ronnie. ‘He really trusted her and her aesthetic: she was minimal, he was minimal. Calvin used to say to me, “I don't want to be ahead, and I don't want to be behind. I want to be there just at the right time.” I think Melanie helped him move forward.’

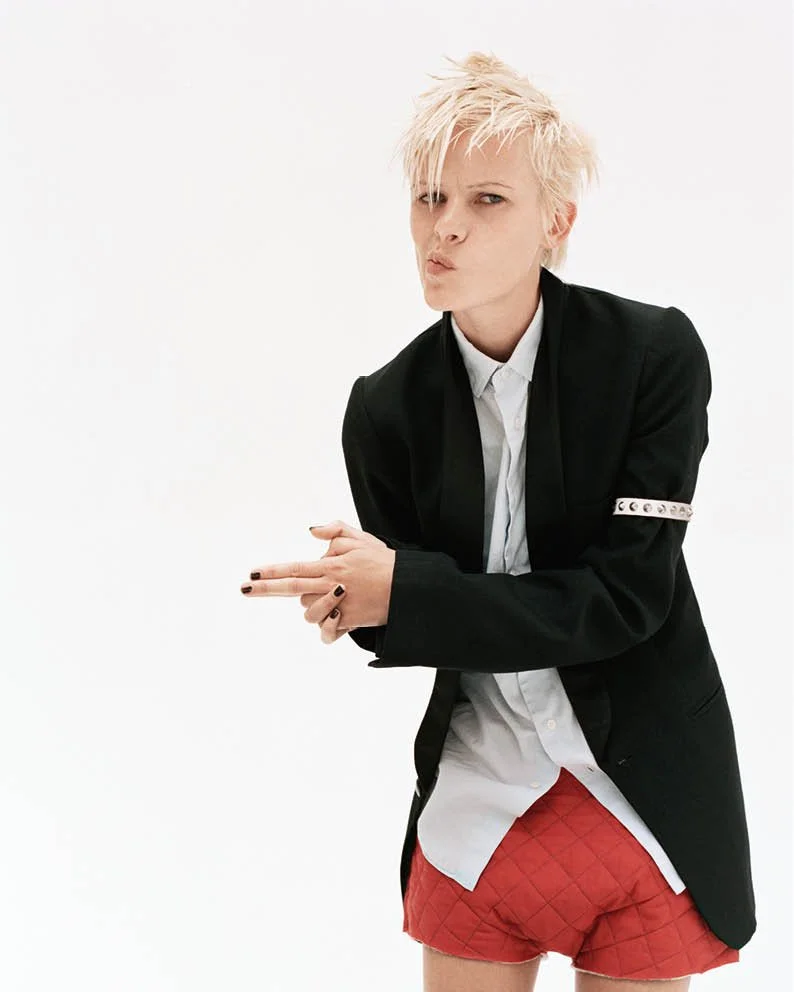

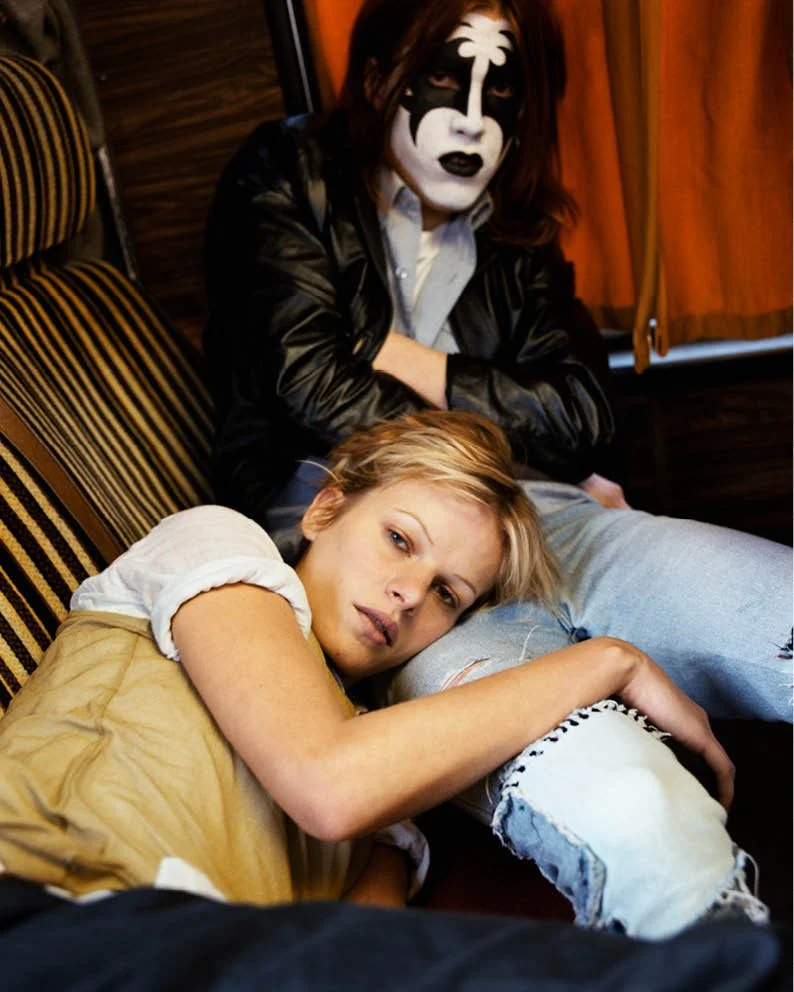

Melanie’s American years were full of wonderful shows and images, particularly with David Sims and Inez and Vinoodh. It was in New York that Melanie’s love of individuality, a sense of character, and a focus on the real person in the picture became allied to a sense of unashamed glamour. The core beliefs remained steadfast, but their outer casing evolved, as did her own image – she herself became every inch the glamorous fashion editor at Harper’s Bazaar under Liz Tilberis. Yet her empathy, personal integrity and radical kindness remained the same. All of this comes to the fore in her working relationship and friendship with Inez and Vinoodh.

‘We met Melanie in 1999, on our first shoot for Bazaar with Kate Moss,’ the duo say, discussing some of their most important work with Melanie. ‘It was this first series with Kate that embodied all of Mel’s qualities in styling and shaped our memories of the shoot: she was subtle, gentle, kind and caring, and she created space and time for everyone to do their best work. It was also incredible to work on the ads for Helmut Lang together, as their creative process was so unique. There was humour, obsessive attention to detail, and a love for the women and men we photographed, seeing each as a unique contribution to the images.’

They continue: ‘She loved a character; she loved to think about the life of the woman we were planning to portray and find clues there that would inform her styling. We started out styling all our shoots ourselves, but realised that a stylist is such a wonderful partner in creating the image from the first seed of an idea onwards; each stylist has their own distinctive approach. Melanie’s styling was never literal but pulled from all sorts of influences to arrive at something fully unique. Today, this role is different again, as sadly, stylists’ wings are clipped by the brands that demand total looks shot and allow for nothing to be mixed or changed. The focus is now more on hair, make-up and image-making because of that.’

‘She loved a character; she loved to think about the life of the woman we were planning to portray and find clues there that would inform her styling.

- Inez and Vinoodh

All Photography: David Sims

All Styling: Melanie Ward

Ultimately, Melanie always returned to Europe, to Paris and Milan, as well as London – her home town – to be at the heart of fashion. In recent years, she spent her time between these cities, where her focus lay on her work with designers.

Here, she worked with a generation of people who had grown up looking at her startling images, something that had fundamentally shaped their sensibilities as designers. Melanie also provided a guiding hand in navigating an industry she had been part of in many ways for many years, with clarity and kindness, as well as talent.

‘I could see myself in how she presented femininity: there was nature and sharpness, with no artifice,’ says Nadège Vanhee-Cybulski, creative director of Hermès. She worked with Melanie from 2015, with her debut collection for the house. ‘I worked with her for eight years. She gave me the confidence to work with Hermès. There was kindness with a sharp intelligence; she was curious and quick with this strong empathy. There was a deep humanity in what she did that was a reflection of who she was. But she was also a woman of no bullshit!’

The last time I saw Melanie was in January 2025, during the final show she worked on: Dior Men’s Winter 2025 in Paris. This would be the last collection Kim Jones would design for the house and the concluding show of his tenure as artistic director. He too is a designer who came to fashion partly through looking at the images Melanie worked on – as a teenager, he had them on his wall.

‘I started working with Melanie for my last Vuitton men’s show in 2017, so our working relationship spanned 2017 to 2025,’ explains Kim. ‘But when I met her, it felt like we had known each other our whole lives; she was sweet, kind and very funny – which always helps. Her modernism always struck me, seeing her work evolve from a kind of rebellion in The Face to a combination of that with a certain polish for Helmut Lang. The collection, with the plackets, collars and outlines of garments, felt like an evolution of the cut-up tees. There was a Seditionaries element that appealed to me immensely. But it was Seditionaries with sophistication, and her work was always effortless and never trying too hard. With me, we spent a lot of time looking at tailoring, at structure and form. Particularly for that last show, we wanted to give the sense of a monumental full stop.’

He continues: ‘Styling was quite a new thing when I was a kid; it was a great influence on my generation. It felt like something in fashion that was no longer the pursuit of posh kids. First there was Ray Petri, then very quickly afterwards there was Melanie. I like people to have a point of view and an opinion. It’s how I work with my team, and I appreciate it with image-makers on the outside. I think the “full look” has killed creativity in an arrogant and silly way, and “advertorials” have done the same. I want to look at my clothes in a new way, alongside other things and with another point of view. There will be so much more to explore in my work as a designer. It’s just a shame it will no longer be with Melanie.’

Looking back now, and hearing Michael Nyman’s ‘Time Lapse’ playing, there was a sense of ending in that Dior show and collection; something grand, sweeping, emotional, yet perfectly realisable, effortless and human. Now, it also feels like a farewell to Melanie and her way of being and seeing. Yet, through her images and inspiration, for those of us left behind and those she encouraged and inspired, Melanie Ward’s legacy lives on.

‘Her modernism always struck me, seeing her work evolve from a kind of rebellion in The Face to a combination of that with a certain polish for Helmut Lang. There was a Seditionaries element that appealed to me immensely. But it was Seditionaries with sophistication, and her work was always effortless and never trying too hard’

- Kim Jones

One of those people is Nilo Akbari, Melanie’s final first assistant, a talent in her own right, and ‘a keeper of the flame’. ‘I feel like fate brought Melanie and me together,’ says Nilo. ‘It was the pandemic. I was in London, and Melanie was in London. I became a first assistant at a time when I didn’t know whether I even deserved it, but Melanie had a way of being open to teaching and helping people grow. This is what she did for me. She let me see and experience things firsthand through her insight. I will forever be grateful to her. She stressed that you needed to play to get things right, not to focus on what others were doing, but on how I was feeling about fashion, and to pave my own way as she did hers. The thing is, I just thought I would have my friend and mentor forever.’

There is a sense of Melanie’s own humanity, effortlessness and grace in the people she worked with and the things she worked upon. There is always a focus on character, on the person in the photograph, on the catwalk, in the clothes. There is a curiosity about and an accentuation of them, because that was what Melanie was about. She didn’t just look at the clothes someone wore; she’d want to know and convey who that person is. It made what she did exist beyond fashion and defined a complete visual culture. Radically timeless, simply complex, human and divine, Melanie’s style delineated the visual approach of an entire era. Her images alone are quite a legacy: monuments to the everyday, embracing the moment, free of nostalgia and simply, as Melanie is, always now.

Writer and Interviewer Jo-Ann Furniss

100 copies of the sold-out Melanie Ward Zine will be available exclusively at Dover Street Market London via IDEA on 21st February.

Perfect Issue 10, with a curated edit of the Melanie Ward Zine by Katie Grand, is available for pre-order now on the website. Link below.